Navigating in VR using free-hand gestures and embodied controllers (ACM VRST 2023)

This is a short paper published at the ACM Virtual Reality and Software Technology Conference 2023, held at Christchurch, New Zealand.

Working on my PhD research, exploring how can technologies of XR (eXtended Reality) can be made accessible for people with sensorimotor disabilities, I am always aware that the hand-held controllers that are assumed as entry points of navigation in virtual spaces (for able-bodied folks) act as the hindering points for people with bodily disabilities to access VR/AR technologies. Specifically, when my disabled collaborators are quadriplegic and paraplegic or do not have the dexterity in their hands which the controllers demand.

VR is an inherently ableist technology that assumes a ‘corporeal standard’ (i.e., an ‘ideal’, non-disabled human body), and fails to adequately accommodate disabled people.

- Kathrin Gerling and Katta Spiel (A Critical Examination of Virtual Reality Technology in the Context of the Minority Body, 2021)

[picture credits: Puneet Jain, in picture: Oliver Sahli]

[picture credits: Puneet Jain, in picture: Oliver Sahli]

Drawing on this motivation of building accessible XR, my research investigated if hand-held controllers are even the best modes of input devices for people who dont identify themselves as disabled (or people who dont have phyical disabilities). How can we identify other body-based methods of input for navigation and movement in virtual environments? How can these able-body bodily movements of navigation thus act a self-critique of ableism embedded within these technologies?

VR is accessible to some bodies but not to others; it is more accessible to some

bodies than traditional gaming and less accessible to others; it does not

foreground the disabled player or attempt universal design in its creation

and execution.

- Adan Jerreat-Poole (Virtual Reality, Disability, and Futurity: Cripping Technologies

in Half-Life: Alyx, 2022)

Alternatively, while body-based input for VR navigation has previously been explored in HCI using external tracking devices, there is little to no work that utilizes the in-built tracking functionalities of the predominant VR headsets (such as Meta Quest 2) for gesture-based navigation in VR. This paper addresses this research gap by proposing five free-hand gestures for 3-D navigation in VR using internal gesture-tracking functionality of Quest 2 headset. Additionally, a qualitative and quantitative comparison is presented between free-hand and controller-based navigation in VR using a custom designed task (with 10 users). Overall, the findings from the task-analysis indicate that while in-built tracking functionalities in VR headsets open doors for inexpensive gesture-based VR navigation, the mid-air hand-gestures result into greater fatigue as compared to using controllers for navigation in VR.

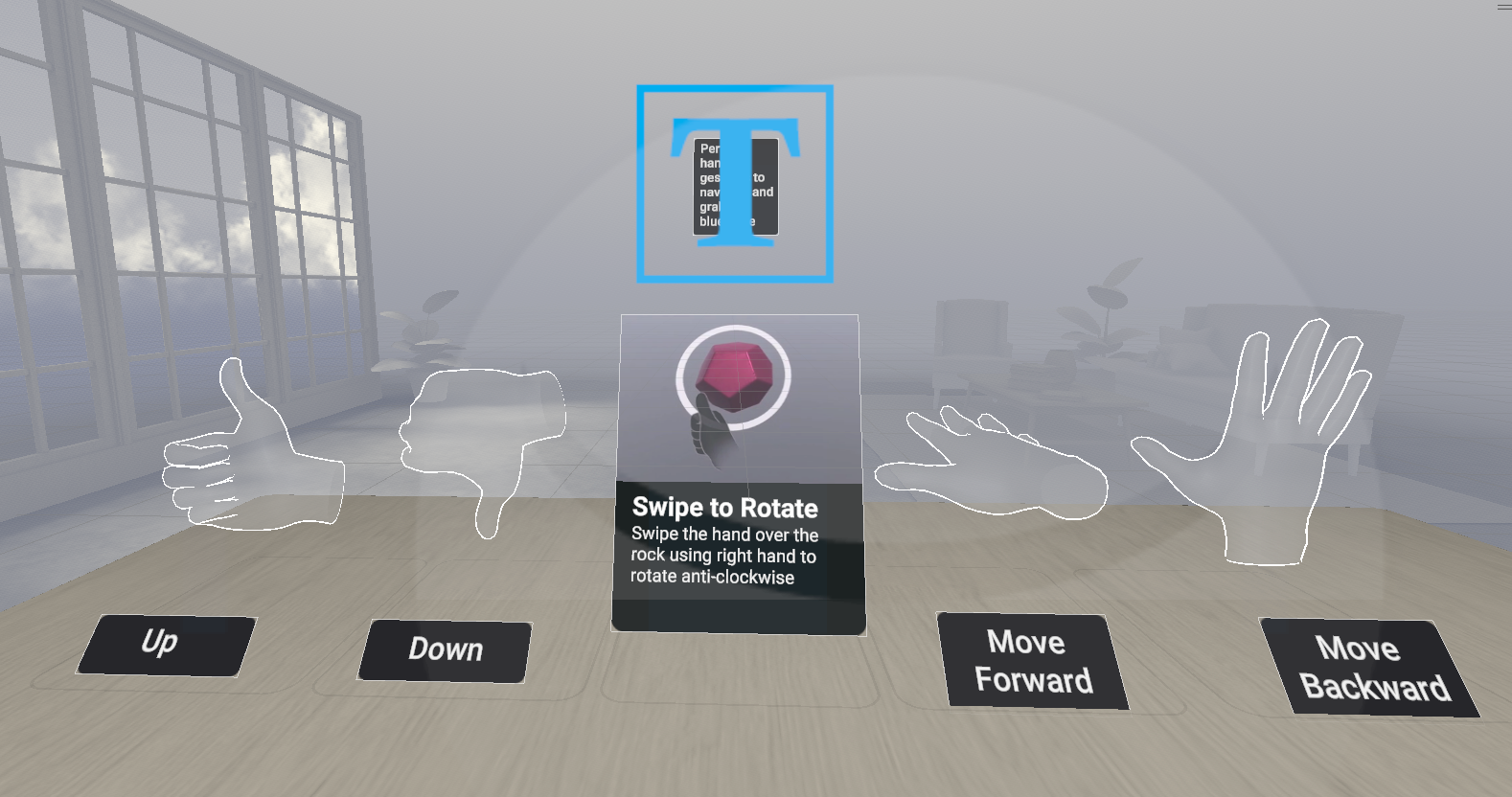

Proposal of 5 free-hand gestures to navigate and move in VR

[Gestures to move up, down, forward, backward, and rotate]

[Gestures to move up, down, forward, backward, and rotate]

Here is the link to read more about the paper: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3611659.3617229